Orange County Litigation Newsletter, Fall 2010

Size Them Up: Picking – or Rather, “Excluding” – a Jury

Clarence Darrow, one of the most famous American lawyers and civil libertarians, wrote in “How to Pick A Jury,” Esquire, May 1936:

“It is obvious that if a litigant discovered one of his dearest friends in the jury panel he could make a close guess as to how certain facts, surrounding circumstances, and suppositions would affect his mind and action; but as he has no such acquaintance with the stranger before him, he must weigh the prospective juror’s words and manner of speech and, in fact, hastily and cautiously ‘size him up’ as best he can.”

In the last 18 months, my team and I tried three long-cause jury trials in Orange County, California. All three trials lasted two months or longer, and all were business cases. In each case, the jury venire was time-qualified for at least 20 trial days. Two of the juries resulted in verdicts in our favor, and the third settled during closing arguments. Jury selection was an important component in the success of these cases.

Demographics

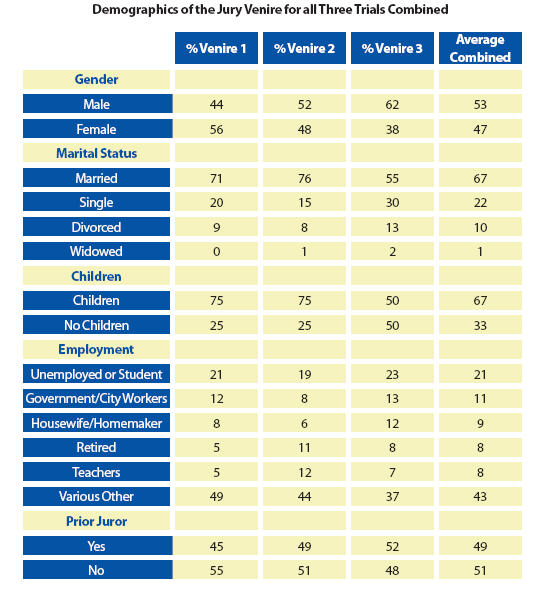

The table on below shows a breakdown of the demographics of the jury venire for all three juries combined. The demographics are fairly typical of an Orange County venire for long-cause cases. Nearly one-third of the venire was unemployed or retired. The shorter the case, the more likely it is that the venire will include a larger percentage of the employed.

A person’s gender, marital status, employment, prior jury experience, and other demographics can affect the way the person perceives things. Jury consultants consistently report that, among other things, long-term, unemployed people; people in service-oriented jobs – sales persons, teachers, waiters/waitresses; union trade workers; people who work in government jobs; and, people with no prior jury experience, tend to favor the plaintiff ’s position. The elderly, or retired people; engineers; doctors; people employed in technical professions; and people with prior jury experience, tend to favor the defendant’s position. But whatever generalizations may be made, demographic profiling should only be used as a guide in the absence of all else, because any particular juror could be the exception to the stereotype.

In the end, the most important jury is the one at hand. Certainly demographics is a tool and should be considered; however, it is far better to ask the questions and make the analysis for each individual potential juror, than to just assume that a potential juror has a particular perspective, simply because of their demographics.

Jury Voir Dire

Jury voir dire is the process of sizing up the potential jurors. Prospective jurors are questioned to find out about their backgrounds and potential biases before being selected to sit on a jury. The scope is broad, as Code of Civil Procedure section 222.5 authorizes a “liberal and probing examination calculated to discover bias or prejudice.” Responses to the voir questions may lead to “for cause challenges” and “peremptory challenges” to exclude the person from the jury panel.

For Cause Challenges

For cause challenges fall into three basic categories: General Qualifications, Implied Bias, and Actual Bias. General Qualifications are requirements expressly listed in Code of Civil Procedure section 203, such as, a juror must be a U.S. citizen, must be 18 years or older, must live in California, must be a resident of the county in which they are being asked to serve, must not have been convicted of a felony or malfeasance in office, must not already be serving as a juror in a trial or grand jury, and must not be subject to a conservator. Implied Biases are also statutory qualifications. Code of Civil Procedure section 229 excludes people who are related to the parties in the litigation by blood or marriage, who are a party’s employer or employee, who have served as a juror within one year of the pending trial, or who have a financial interest in the outcome of the trial. And, Actual Bias is “the existence of a state of mind on the part of the juror in reference to the case, or to any of the parties, which will prevent the juror from acting with entire impartiality, and without prejudice to the substantial rights of any party.” Code of Civil Procedure section 225(b)(1)(C). For example, an Actual Bias would include people who state that it would be difficult for them to keep an open mind, admit that they are biased, admit to having strong opinions showing bias, or admit that it would be difficult for them to be fair.

The defense has the first challenge for cause. There is no limit on the number of for cause challenges. It is reversible error for the court to fail to exclude a person with a bias or prejudice; however, to get a reversal, the party must first have exhausted all of its peremptory challenges.

Peremptory Challenges

Peremptory challenges allow potential jurors to be excused without giving any particular reason. When an attorney exercises a peremptory challenge for a potential juror, the court must remove that juror. The concept is that peremptory challenges act as a safety valve to permit an attorney to remove a potential juror who has individual characteristics which the attorney believes might make them sympathetic to the opposing party.

Plaintiff has the first peremptory challenge. In California state courts, each party gets six peremptory challenges (eight, where there are several parties on the same side), plus the number of alternate jurors to be used in the panel.

Objections

Although the statute authorizes “liberal and probing examination” of the potential jurors during voir dire, there are limitations. Certain inquiries are improper. They include making statements to indoctrinate the jury as to specific positions of the parties; inquiring about the jurors’ comfort, as it is considered to be pandering to the jury; relaying information about the personal lives and family of the parties or their attorneys; and, arguing the law.

Improper questions or comments may be handled in two ways. The first is to make an objection in open court, which I typically do if the question or comment is unmistakably improper, such as a question that clearly attempts to pre-condition the jury. The advantage is, that if the open court objection is sustained, the offending attorney may lose favor with the jury. And, if the objectionable conduct continues, repeated sustained objections could likely negatively impact the jurors’ views of the attorney during the very time the attorney should be building a strong rapport with them.

The second technique is to interrupt and ask for a side bar. I typically use this approach for close call objections as it allows me to more fully elaborate my concerns to the judge at side bar and to measure the judge’s reaction and viewpoint. Because it is a close call, if the judge disagrees with me and overrules my objection, it saves me any embarrassment from being overruled, since, generally, after the side bar, the court will simply say, “please continue.” At a minimum, the side bar objection allows me to sensitize the judge to my concern, and in the event that the offending attorney then goes even further with the inappropriate questions and comments, the judge may be more likely to sustain my subsequent objections.

The Voir Dire Questions

Uncovering adverse bias is the most important part of sizing up potential jurors. One or two strong adverse jurors can cost everything, and all of the work done in the litigation for the prior year or two is for naught. Research continues to confirm that jurors’ long-held beliefs are the greatest factor in determining how they will decide a case, despite the lawyers’ performances. That is because people filter information and tend to ignore or discount that which is incompatible with their beliefs. For example, most people watch the cable news stations that are most consistent with their own political perspectives. And when people listen to political debates, they tend to focus on and favor the points made by the candidate they supported, even before the debate began.

To plumb their beliefs, the atmosphere during voir dire must encourage candor. The potential jurors must feel that it is safe to talk and to express themselves; that they will be allowed their opinions without argument. Voir dire should be a conversation, not a debate. Indeed, negative responses from potential jurors should be validated. I like to think of the process as assisting potential jurors in exposing their biases. They need to be encouraged to reveal secret negative feelings so they don’t end up on a jury panel improperly.

Concerns about getting a negative response from a question posed to a potential juror and that response then tainting other potential jurors are unfounded. Studies show that tainting other members of the panel is extremely rare. Heartfelt views and experiences are not suddenly changed just because some unknown person sitting nearby says something negative.

Identifying Adverse Biases

Preparation is the key. The strengths of your case, and especially its weaknesses, must be clearly considered and defined. Voir dire questions should be formulated around the strengths, but particularly around the weaknesses. The goal is to identify biases against your position.

One technique for identifying adverse biases is to ask questions from the perspective of the opposing party. Those potential jurors who respond favorably to such questions are prime candidates for exclusion. For example, depending on the kind of case, find out which jurors agree with one of the statements that “employers are generally focused more on the bottom line than the people who work for them,” or “it’s ok to break a contract if it would be far more expensive to perform than originally considered,” or “stockbrokers are more concerned about generating commissions than high quality investments.” Follow up with those potential jurors who indicate that they agree with such statements to find out why they feel that way, and how strongly they feel about it. Their responses to follow up questions such as “what was your reaction to that?” or “how long ago was that?” or “has that happened to you more than once?” get closer to finding out their deep-seated biases. Test resolve. Look for entrenchment. For example, a potential juror who states that they believe lawsuits have a negative impact on the economy, might be asked “if someone in your family was badly injured by a product, do you think it would be appropriate to sue the company that made it?” or, for a potential juror who has agreed with the statement that a “deal is a deal,” they might be asked “do you believe that there is ever any excuse for not keeping a promise?”

When biases are uncovered and the extent of them measured, move on. Mission accomplished. Do not ask an unfavorable juror if they can be “fair and impartial.” Typically, they will say that they can, and you may have just elicited an answer that will prevent that juror from being excluded for cause. When you later excuse them by peremptory challenge, it becomes apparent that you are trying to stack the jury. On the other hand, if there is a strong, favorable juror, consider asking that juror whether they can be “fair and impartial.” It is unlikely that a strong favorable juror for your position would have gone unnoticed and not excluded by the other side. Knowing that, there is no downside in highlighting how fair and impartial this favorable juror can be. Then, when the other side excludes that juror, it may appear that the other party is attempting to stack the jury.

Identifying Silent-types and Leaders

Be mindful of the silent ones. When questions are posed to the entire panel, studies show that nearly 30% of the prospective jurors do not respond at all. They don’t raise their hands, nod, or respond one way or the other. And since follow up questions are directed to the responders, the silent ones are inadvertently ignored. This silent group of non-responders is important. In post-trial interviews, it turns out that nearly 20% of the silent ones actually had biases that would have allowed them to be excused for cause, even without using a peremptory challenge. For this reason, keep track and ensure that every single juror is carefully interviewed.

Throughout the course of the voir dire, keep a sharp eye out for leaders. Leaders will drive the deliberations and possibly the verdict. Unfavorable, strong leaders are the most perilous to your case. These potential jurors need to be vetted and excluded if possible. Leaders are the potential jurors who unhesitatingly express their opinions, communicate well, exhibit confidence, and have that indefinable magnetism. Additionally, potential jury leaders are those people who have had several prior jury experiences, who have case-related expertise, are managers, are attorneys, or are highly educated.

There is no perfect juror – at least one who remains on the final panel. The jurors who would be tailor-made for one side are generally excluded by the other side. So in the end, lawyers do not really “pick” jurors, they try to size them up to “exclude” the ones they think are the most unfavorable to their case.

Mark S. Adams, a partner in the Litigation Department of JMBM’s Orange County office, focuses his practice on business litigation including, contracts, products liability, corporate and partnership disputes, and employment litigation. He has tried numerous cases in state and federal courts, and in domestic and international arbitrations. Contact Mark at MarkAdams@jmbm.com or 949.623.7230.

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

Los Angeles Real Estate Litigation Lawyer Jeffer Mangels Butler & Mitchell LLP Home

Los Angeles Real Estate Litigation Lawyer Jeffer Mangels Butler & Mitchell LLP Home